Pocket watches date back to the 16th century. Early watches, or “pocket clocks,” only had an hour hand; the minute hand came along in the early 17th century. The second hand didn’t become common until the 18th century. Technical advances continued, and in the 1820s, watches using the lever escapement became accurate to within a minute a day.

Until the wristwatch was developed based on the trench watch of World War I, pocket watches set the standard for portable timekeeping, style, and status. Let’s take a look at some instances where pocket watches changed our understanding of history, and history caused pocket watches to change.

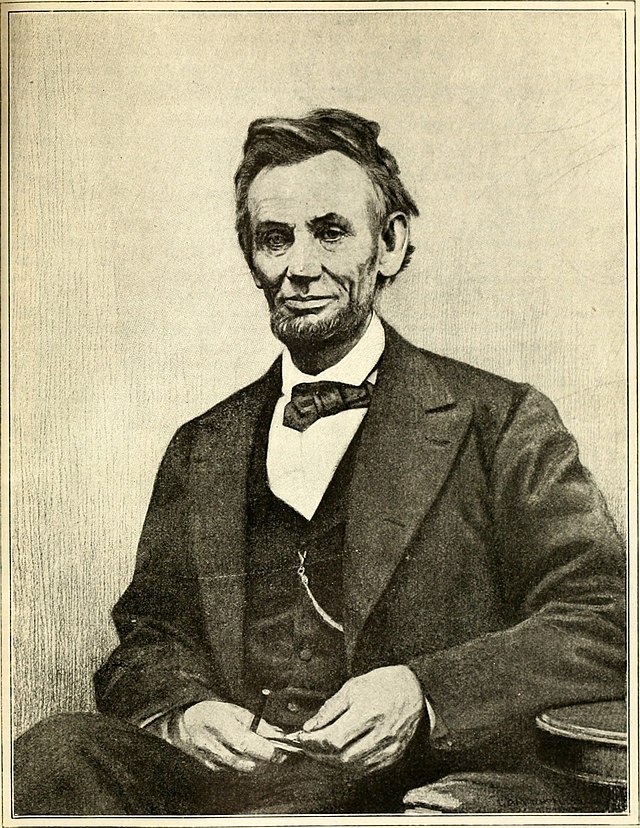

The Hidden Message in Lincoln’s Watch

On February 12, 2009, Abraham Lincoln’s 200th birthday, Harry Rubenstein, chief curator of the Smithsonian’s exhibition “Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life,” got a call from Douglas Stiles, a 59-year-old attorney from Waukegan, Illinois. Stiles claimed his great, great grandfather, an Irish immigrant and watchmaker Jonathan Dillon, had etched a secret message inside President Lincoln’s pocket watch just as the Civil War broke out.

Further, Stiles wanted to know if Rubenstein would be interested in bringing in an expert craftsman to disassemble the 150-year-old English gold watch, which had been in the museum’s possession for more than 50 years, to check. Other than family lore, Stiles’ only evidence was a 1906 New York Times article in which Dillion was interviewed while on jury duty.

In the article, Dillon tells a reporter that he was working on Lincoln’s watch at M. W. Galt & Co. on Pennsylvania Avenue on April 13, 1861, when his boss, Mr. Galt, came into the workshop and announced that the rebels had attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

“I was in the act of screwing on the dial when Mr. Galt announced the news. I unscrewed the dial, and with a sharp instrument wrote on the metal beneath: ‘The first gun is fired. Slavery is dead. Thank God we have a President who at least will try. Then I signed my name and the date.’”

Rubenstein was intrigued and decided to have the watch opened and examined. I guess he had not seen Geraldo Rivera open Al Capone’s empty vault on a two-hour live television special in 1986.

A month later jeweler George Thomas – surrounded by photographers and Stiles, his wife Betsy and his brother, Don – took the watch apart and delicately lifted the watch face away to reveal the following messages:

“Jonathan Dillon April 13-1861 Fort Sumpter [sic] was attacked by the rebels on the above date. J Dillon.”

“April 13-1861 Washington. Thank God we have a government. Jonth Dillon.”

Not exactly the same message Dillon told the NY Times reporter but human memory is seldom a precision instrument.

At some point, two additional people added the following inside Lincoln’s watch.

“LE Grofs Sept 1864 Wash DC” and written on a brass lever “Jeff Davis.”

You know how it is. Once a graffiti artist puts their tag on a highway overpass, all the hotshots want in on the action. Let’s just be glad the watch wasn’t serviced any more often than it was.

The Century Plus Secret in the Civil War Sub Captain’s Watch

We don’t know where Lt. George Dixon, commander of the submarine CSS H. L. Hunley, was born. We do know that he was a steamboat engineer on the Mississippi River and settled in Mobile, Alabama, before the U.S. Civil War began. In Mobile, he joined the Masonic lodge, a local police force called the Mobile Grays, and in 1861 enlisted in the 21st Alabama Infantry.

He fought at the Battle of Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee, where he sustained a wound to his left leg. Dixon credited a Federal $20 gold coin with partially deflecting the bullet and saving his leg and possibly his life. He had the following engraved on the back of the coin: “Shiloh April 6, 1862 My life Preserver G. E. D.” The regiment returned to Mobile and was tasked with garrison duty at the port, where Dixon became interested in the submarine, or “fish boat,” being built by Horace L. Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson.

On February 17, 1864, Dixon commanded the Hunley on her first and only attack on the Union Navy. The Confederate submarine sank the USS Housatonic in a clandestine night attack in Charleston Harbor. This was considered the first successful submarine attack on an enemy warship.

In this situation, “successful” is relative; the submarine’s crew was presumably killed instantly by the explosion. The craft’s spar torpedo consisted of a copper cylinder containing 135 pounds (61 kilograms) of black powder attached to a 22-foot (6.7 m)-long wooden spar. This outcome is still debated by some, but it is hard to imagine that an explosion of that size in that proximity to the sub would not be fatal to all on board.

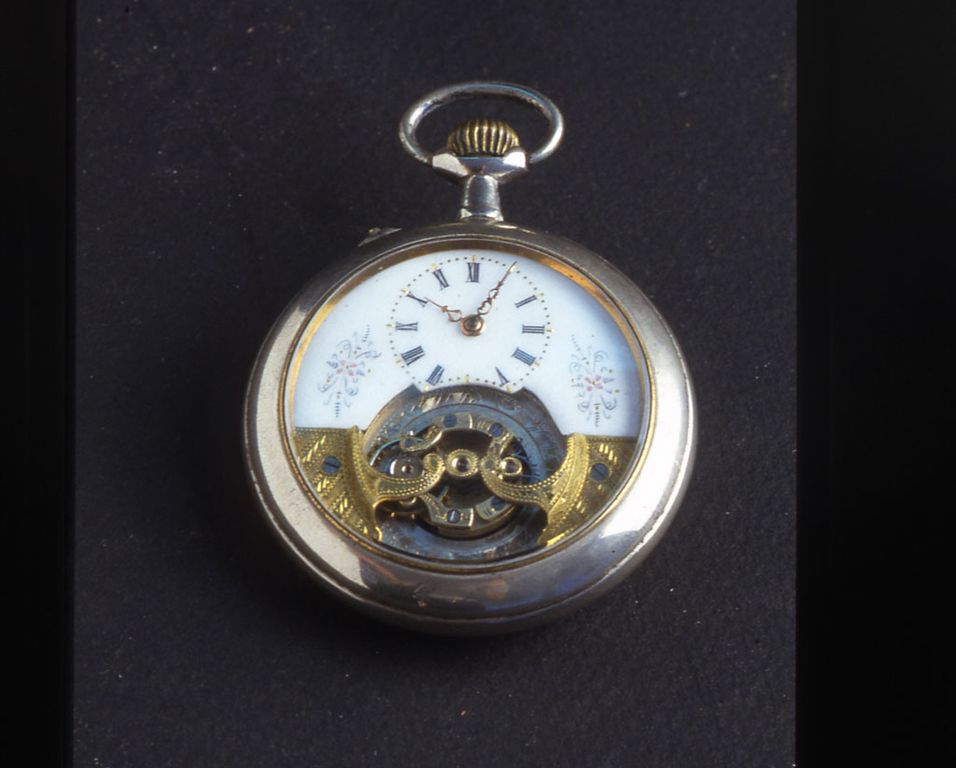

Dixon must have been a man of some wealth based on the personal effects recovered from his position beneath the forward conning tower. These included silver suspender buckles, diamond-studded jewelry, Dixon’s keepsake “Shiloh coin,” and most importantly, an 18-carat gold pocket watch.

When scientists opened the watch, they found the hands stopped at 8:23. This appears to support the theory that the submarine sank during its attack on a Union warship. Experts had theorized that the Hunley went down between 8:45 and 9:00 p.m. Captain Green, commander of a nearby Union ship, the USS Canandaigua, documented that the Housatonic was sunk at 8:45 p.m. “by a rebel torpedo craft.” This was before railroad travel brought about universal time standards; the Union’s standard time was about 20 minutes ahead of Charleston’s local time, so the two times match up and seem to indicate that the Hunley sank with the Housatonic. The United States standardized time zones in 1883.

Railroad Grade Pocket Watches Set a New Standard

In the era before automated switching with trains traveling in opposite directions on the same track, departure, and arrival times were critical. Discovering that the light at the end of the tunnel is an oncoming train is even more dangerous and terrifying if you’re riding toward it on a train when you see it.

The Great Kipton Train Wreck on April 19, 1891, changed railroad timekeeping, led to standards for the railroad grade watch and created a timepiece inspection system. A fast mail train eastbound collided with a passenger train, the Toledo Express, headed westbound at the Kipton, OH, train station, about 40 miles west of Cleveland. The engineers for both trains and six postal workers on the mail train died. Both locomotives were demolished, wooden mail cars were smashed into kindling, and a fireman, multiple passengers, and people at the station were injured.

Investigators concluded the crew of the Toledo Express was at fault. Their train was late and should not have left for Kipton, knowing the express mail train was coming on the same track. They failed to make it onto a siding in time to let the mail train pass safely.

“But the engineer’s watch stopped four minutes and then began running again, a little matter of life and death of which he was unconscious,” said Webb C. Ball, the man tasked by the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad to investigate time and watch conditions on the line in a copyrighted 1910 article that ran in newspapers nationwide.

His efforts resulted in the watch performance and inspection standards of 1893. According to the Ohio Historical Marker at the Kipton train wreck site, the phrase “Get on the Ball” is a reference to his work.

Here is a partial list of railroad grade watch standards:

- Maximum variation of 30 seconds per week (about 4 seconds a day) which was impressive accuracy for the period

- Watch adjusted to at least five positions: Face up and face down (positions a watch would take on a flat surface); then crown up, crown left, and crown right (positions a watch would take in a pocket). Occasionally a sixth position, crown down, would be included.

- Only open-faced dials with the stem at the 12 o’clock position with bold Arabic numerals, second dial, thick hands

- Minimum 17-jewel movement

- It had to be lever set to avoid inadvertently changing the time when winding the watch.

A standard watch inspector would check a railroad worker’s watch twice a month. Before starting a trip, crews had to check their watches with “standard clocks” at stations or roundhouses. Conductors and engineers compared watches, and so did the engineer and fireman. If someone’s watch wasn’t keeping good time, they had to get a loaner watch. Crew members could buy watches through monthly payments through monthly payroll deductions.

Pocket Watch Comeback

The steampunk movement is breathing new life into pocket watches. New mechanical and battery-powered watches are available from online retailers. Antique pocket watches are also quite affordable for anyone who wants a decorative piece, functional historical item, or cosplay icon.

My Personal Pocket Watch Connection

My fascination with pocket watches goes back to my grandpa, Henry Massey, who lived near Barnard, NC, in Madison County.

My father was an Army Sergeant, and almost every Christmas and Fourth of July, we would pile ourselves and a startling amount of our personal belongings into our car, a blue two-door 1968 Ford Galaxie 500, and drive from wherever he was stationed to my grandpa’s house so my mom and dad could check back in with their families.

One summer, we drove in from Daleville, Alabama, with a 14-foot Sears aluminum Jon boat strapped to a rack on the top of the car; my father used it to fish and run a trotline in the French Broad River.

My grandpa lived in a small, uninsulated house without running water beside Big Pine Creek. It was lit by bare light bulbs and heated by a coal/wood stove. His entire stock of household appliances included a wood cook stove, a small refrigerator, and an AM radio. He did not have or want a telephone. Even back then, it seemed like he lived in a different world, a 19th-century man living somewhat grudgingly in the 20th century.

He was a retired railroad section hand who had made his living laying and maintaining track. He seemed reasonably comfortable being pressed into service as a babysitter for two small children. I would describe his caregiving style as Well, if the kids aren’t back in an hour or so, I’ll go look for them.”

His uniform of the day was a railroad engineer’s cap, a long-sleeve collared shirt, and Pointer Brand bib overalls. A pair of leather brogues completed the ensemble. In the wintertime, he added woolen long johns with the rear flap, or “drop seat,” like in old cartoons.

Through the hole at the top of his overalls’ bib was a black braided leather strap that was attached to his pocket watch, which resided in a specially designed pocket. I recall sitting beside him on his couch with my head leaning against his chest and the rhythmic, steady ticking of that watch lulling me to sleep.

I do not know the maker, model, or year of his watch. I remember that it was an open-face, stem-wind watch, and it had a sub-dial at the bottom for seconds that I found particularly fascinating. It felt impossibly heavy in my childhood hand and seemed solid as granite.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. Click on one of the social sharing icons below. Do you have a hot tip on a cold case? Got a topic you’d like to see covered? Want to nominate a moonshine king, Appalachian outlaw, legendary lawman, massive manhunt, or blue-ribbon bloodhound for a future post? Clue me in with an email to editor@blueridgetruecrime.com.

Check out my new book, Blood on the Blue Ridge: Historic Appalachian True Crime Stories 1808-2004, cowritten with my friend and veteran police officer, Scott Lunsford on Amazon. Buy it here! Download a free sample chapter here!

I also have a Substack newsletter, A History of Bad Ideas, where I write about poorly thought-out ideas, misguided inventions, and dire situations throughout history created by people who frankly should have known better.

Sources:

Collectors Weekly. “A Short History of the American Antique Pocket Watch.”

Post and Courier (Charleston, SC), June 3, 2022: Page 1: “Hunley captain’s pocket watch goes on display: ‘It brings more of a personal effect.’” by Kailey Cota

Smithsonian Magazine, March 10, 2009: “Secret Message Found in Lincoln’s Watch, by Beth Py-Lieberman

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lincolns-pocket-watch-reveals-long-hidden-message-57066665/

Associated Press, March 10, 2009: “At long last, Lincoln’s watch yields a Civil War message. by Brett Zongker.

New York Times, Monday, April 30, 1906, Page 7 “Who has Lincoln’s Watch”

Railroad chronometer – Wikipedia. “Railroad Chronometer – Wikipedia.”

The Great Kipton Train Wreck, National Postal Museum, April 22, 2013. “The Great Kipton Train Wreck” by Nancy Pope, Historian and Curator.

Clyde Enterprise, OH,· Saturday, April 25, 1891, Page 2 “Terrible Lake Shore Wreck”

Los Angeles Times, CA, Sunday, January 16, 1910, Page 115: “Keeping Correct Time on Great Railroads” by James B. Morrow.

Lt. George E. Dixon https://www.hunley.org/george-dixon/

Artifacts Belonging to Doomed 19th Century Submarine Captain Conserved https://www.hunley.org/artifacts-belonging-to-doomed-19thcentury-submarine-captain-conserved/

RailsWest.com: Accurate Railroad Watches Allow Trains to Move Safely