An unknown NC moonshiner became the subject of books, manhunts, and buckshot battles.

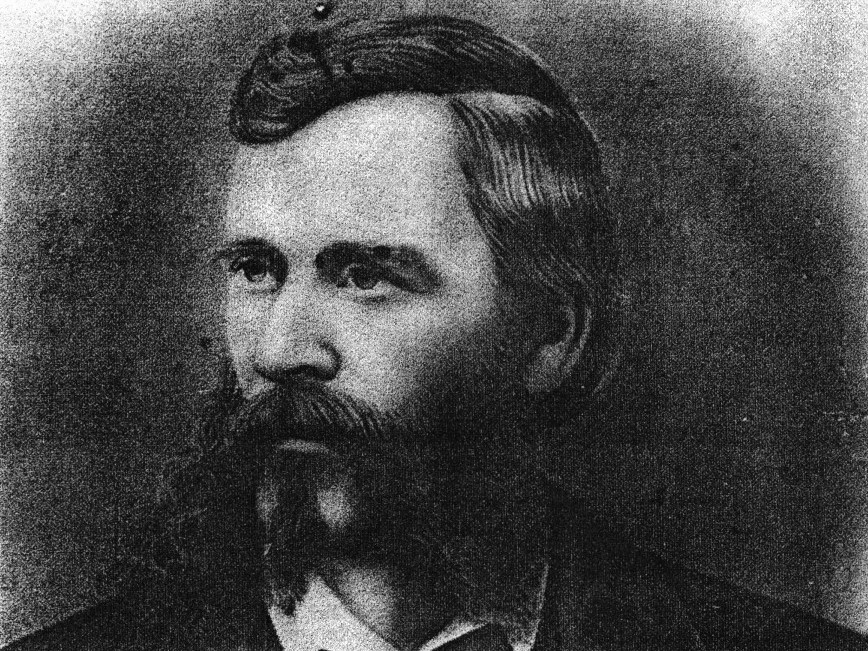

“Major” Lewis Redmond had many titles: moonshiner, bootlegger, killer, and most impressively, King of the Moonshiners. Playwright Gary Carden may have given Redmond his most colorful moniker, the Prince of Dark Corners, which is the title of his play based on the outlaw’s life. Major was a nickname said to have been given to him by confederate soldiers because he hung around their camps when he was a kid.

Redmond is known for two things: moonshining and audacious defiance of revenue agents. Many saw him as a folk hero, an Appalachian Robin Hood. Redmond offered much to admire and much to condemn. Equal parts hero and villain, he was a product of his time and place, the Blue Ridge Mountains during the Reconstruction Era.

Mountaineers revered Redmond and felt he was fighting for them against an encroaching and unpopular federal government. Revenuers saw him as an elusive hard case with a terrifying habit of making unexpected appearances in their lives.

From Bruce Stewart’s King of the Moonshiners: Lewis R. Redmond in Fact and Fiction:

“More than any other individual moonshiner in southern Appalachia, Redmond captured the imagination of middle-class Americans during the late nineteenth century. Like Billy the Kid and Jesse James, he became a legendary figure, reflecting people’s hopes, needs, and fears. Most mountain residents (and other Southerners) viewed him as a folk hero, an outlaw who valiantly fought against the Bureau of Internal Revenue and its ‘infernal’ liquor tax. He supposedly killed in self-defense and for a noble cause: to protect his community from an ‘oppressive’ federal government. Many people from outside the South, however, insisted that Redmond was a violent criminal, the product of an uncivilized region that required reforming.”

He had a meteoric rise to fame, going from being an unknown farmer, moonshiner, and bootlegger in 1875 to being an outlaw featured in newspaper articles in at least 18 U.S. states in 1878, from Louisiana to Minnesota and from Virginia to Kansas. He even made the front page of the New York Times. The problem with a meteoric rise is that it is often followed by a meteoric crash. His outlaw career was punctuated with shout outs in newspapers of the day and shootouts with revenue officers. Redmond would injure multiple law enforcement officers, at least one fatally, and wind up on the receiving end of bullets and buckshot himself.

Going Viral in the 1870s

In June 1878, the Charleston News and Courier dispatched Reporter C. McKinley to northwest South Carolina to find and interview the elusive outlaw. McKinley succeeded and it was his series of articles that gained Redmond national attention and much of the information used to write this post.

McKinley, who wrote under the byline “C. McK.”, was clearly sympathetic to Redmond and his cause, and the articles he wrote strayed into hero worship at times. McKinley credits him with paying the land taxes for poor families, providing a wagon for 10 old men to get to the polls to support Wade Hampton, who ran successfully for S.C. governor, and supporting his three sisters.

Northern papers took a dimmer view of Redmond’s exploits. A July 15, 1878, New York Times article titled “Democratic Moonshiners” devoted almost two columns to Redmond’s activities, which according to their “Occasional Correspondent,” included innumerable violations of revenue laws, jailbreak, overcoat theft, setting an ambush, murder, attacks on (revenue) officers, and the whipping and maiming suspected informants. The article also refers to Addie Ladd, who Redmond would marry in October of that same year, as a “concubine” and described her as “an illiterate, coarse, mountain woman.” Taking the article as a whole it sounds like the “Occasional Correspondent” either had a way more than credible knowledge of Redmond’s daily activities or was engaged in a sell-rumor-as-fact scheme.

In 1879 Redmond was featured in a dime novel with the lengthy and unlikely title: The Entwined Lives of Miss Gabrielle Austin, Daughter of the Late Rev. Ellis C. Austin, and of Redmond, the Outlaw, Leader of the North Carolina Moonshiners, supposedly written by Bishop Edward B. Crittenden. While the book purports to be a true story, it is a completely fictional 19th-century bodice ripper that proved so popular that it went through multiple printings. It is in the public domain and available online.

Two years later, in 1881, R. A. Cobb, of Morganton, N.C., published a more factual 32-page pamphlet entitled: The True Life of Maj. Lewis Richard Redmond, the Notorious Outlaw and Famous Moonshiner. In it Cobb gives the following scathing summary of Entwined:

“In this blood-and-thunder pamphlet, Redmond kills a United States Commissioner, Irwin C. McDowell, in the post office at Asheville, N.C., kills the Hon. Arthur Spates, a judge of the Circuit Court, in the courthouse at Franklin, Macon county, and has a Charleston company of infantry and the ‘Charlotte Grays’ detailed by Governors Vance and Hampton to capture him. Now there is a post office at Asheville, and there is a courthouse at Franklin and the names of the Governors are right, the rest is a bad sort of a lie badly told.”

If you’re looking for a name for your 90s cover band please do consider going with “blood-and-thunder pamphlet.” Works even better if it’s an 1890s cover band. Plus you’ll have a charming backstory about a fake bishop. Here are the facts of Redmond’s astounding story as best as I can piece them together from multiple book and newspaper accounts.

No Rules in A Gunfight

His outlaw career began on March 1, 1876, when he was confronted by Deputy U.S. Marshal Alfred Duckworth near Brevard, North Carolina, in Transylvania County.

Redmond, who was 21 years old at the time, had been making and transporting moonshine for some time. The authorities became aware of this and issued a warrant for his arrest. Duckworth and another deputy, D. M. Landford, happened upon him and his future brother-in-law, Amos Ladd, driving a wagon in the East Fork section of the county. Duckworth ordered them to stop and announced that he had a warrant for Redmond’s arrest.

In some accounts, it was just the four of them. In others, there was a crowd on the road. In the most common version of the story, Redmond agreed to surrender or talked Duckworth into holstering his pistol and then shot the deputy in the throat with a derringer that he either grabbed from or was handed by Ladd. Book authors, Stewart, Arthur, and Cobb all record the shooting that way in their writing. Jim Bob Tinsley in The Land of Waterfall mentions a jury of inquest held the day after the shooting that found “The said Alfred F. Duckworth was shot and murdered by one Major Redmon.”

Redmond in an interview with McKinley in 1878 stated that Duckworth had a cocked pistol pointed at him when he grabbed a derringer from Ladd and shot the deputy. Redmond and Ladd ran. Duckworth attempted to pursue but collapsed and died shortly afterward. Redmond further stated that Landford shot at him as he fled.

“I started up the road and had gone about thirty yards when Landford shot at me and kept shooting until he had shot four times,” Redmond said. “He missed me every time, and I thought if that is the best you can do I will go back and kill you with a rock!”

Whichever account you go by, Redmond took on two armed officers with a one-shot pistol designed for use across a card table and escaped unscathed. He crossed over into South Carolina and began operating out of Pickens County which at that time was part of a region known as the Dark Corner or Dark Corners.

Capturing, Keeping, and Contending with Redmond

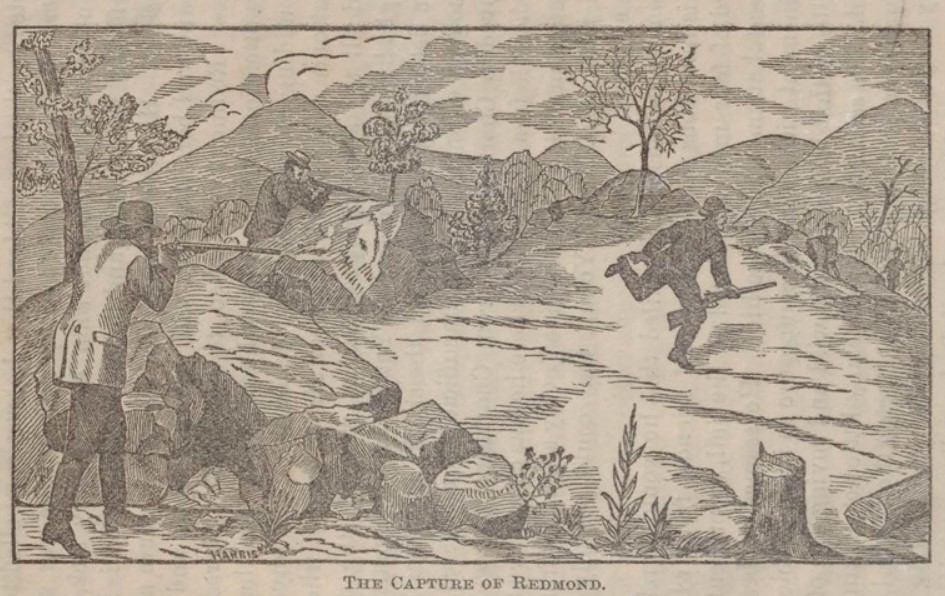

Two related events demonstrate Redmond’s legendary resourcefulness, daring, and will to resist revenue agents: his momentary capture in January 1877 and his subsequent raid on Deputy U.S. Marshal E. H. Barton.

On Thursday night January 11, 1877, the revenuers set a trap for Redmond and Ladd. Deputy U.S. Marshal Van Hendricks posed as a buyer and set up a meeting at an abandoned house in Pickens County to purchase 25 gallons of moonshine whiskey.

Redmond and Ladd arrived early, kindled a fire in the hearth, took off their boots, and took a nap while they waited. Around half past midnight Hendricks and John Jamison, also a revenue agent arrived and engaged them in conversation. At a prearranged moment the rest of the posse, E. H. Barton, W. F. Gary, and Charley White rushed through the cabin door with drawn guns and surrounded the two moonshiners.

“Just then a crowd of men, who had been waiting outside, burst open the door and rushed in on me and surrounded me,” Redmond said. “There was a big light in the fireplace, and I saw a dozen guns were cocked and pointed right at me.”

“Several of them jumped upon me at once, and held me down and pinioned my arms, and then they turned me over on my back, and Barton and Gary tied my wrists close together.”

Redmond alleged that while he was tied, he was handled roughly and kicked by Barton. Barton said this didn’t happen. After he regained his feet, Barton searched him and took a pocketbook which Redmond claimed contained $186.

At this point, Redmond asked for his boots. When Barton bent to grab them, he let go of the end of the rope tied to the prisoner’s wrists and Redmond made his move. With his hands tied in front of him, he was able to knock two of the deputies off balance, kick at another who gave way, and pushed through the others to the cabin door.

“I jumped out of the door like I had been greased,” Redmond said. “They dashed out after me. Bang, bang, went their guns. The balls struck all around me and knocked up the snow.”

(Editor’s note: It was common at that time for people to refer to bullets as “balls.” The transition from muzzleloading firearms that fired round balls or the more advanced Minié ball, a conical lead bullet, to black powder cartridges that look and operate like today’s ammunition was a recent development.)

He ran around his wagon, gathering the rope with his hands so it wouldn’t trip him, jumped over a chestnut log, vaulted a fence, and made it into the woods. He found himself standing in the snow in his stocking feet, unarmed, with no coat or hat. Any reasonable person would have had two concerns: finding shelter to avoid freezing and getting as far away from the area as possible. But Redmond was not in the mood to be reasonable. He had lost his friend, his pocketbook, the whiskey, the wagon, a team of horses, his guns, boots, coat, shawl, and hat. He was set on rescuing Amos and getting some payback on the revenue officers who had taken his friend and his belongings.

Redmond ran to a nearby house and was able to talk the owner into letting him have a coat, a hat, shoes, a shotgun, and ammunition in the form of buckshot. He ran to the road. He knew the route the revenue officers would have to take and planned to intercept them.

The revenuers were delayed by their search for Redmond, having to hitch Redmond’s team up to his wagon and having a bit of difficulty with one of his two mares. Consequently when they came down the road with their wagon pulled by a single horse, and the confiscated wagon with the whiskey, they drove right into Redmond’s sights.

As the revenue wagon came into range, silhouetted against a snowbank, Redmond leveled the shotgun and fired. Someone in the front wagon returned fire, then everyone abandoned that wagon, ran up a bank, and took cover in some bushes. Unable to spot Redmond in the darkness, they hurriedly remounted the wagon and drove on. Redmond had to cease fire for fear of hitting Amos. Redmond pursued on foot, running beside the road.

The wagons stopped at the next house, and Amos, who had managed to untie his hands during the melee, was able to slip away. Shouts of “He’s gone. He’s gone.” and several shots into the darkness alerted Redmond to his partner’s escape. The posse entered the house and Redmond whistled for Amos, who found him and related that Barton and Hendricks had been hit in the exchange of gunfire.

The January 18, 1877, Anderson Intelligencer confirms that two U.S. Marshals had been wounded “While in pursuit of Redmond through the woods.” Barton was hit in the thigh and Hendricks in the chest.

I can’t help but wonder if Amos was elated that his friend was working to free him or terrified that he would be shot by accident or killed if the wagon he was riding in overturned. It seems certain that the officers were unnerved to have the snowy country lane they were traveling turned into a maniac’s shooting gallery. After briefly considering rushing in, cutting the traces, and recovering his horses, Redmond decided to call it a night.

A Small Matter of Repayment

On Saturday morning, January 20th, Redmond along with either nine or 12 men rode to Barton’s house and confronted the deputy, demanding the return of the $186 taken from him and his two mares.

Barton told him the money had been deposited in the Greenville Bank and the horses were in a livery stable there as well. According to Redmond’s account, Barton offered to go to Greenville and get them or allow Redmond to send some of his men to fetch them. Redmond declined the offer probably realizing that what he would get back from Greenville was an armed posse and demanded that Barton make good on the debt. Barton gave him a check for $100 and two of his horses. Mrs. Barton traveled with Redmond to Easley Station to cash the check

Barton gave Redmond two of his own horses and a check for one hundred dollars. Mrs. Barton went with him to cash the check at Easley Station. He sent her home with an escort and with one or both of the horses, accounts vary on this point. Redmond claimed to have sent both horses back with her. Barton resigned his position in the Revenue Department in March 1877.

Bullets, Buckshot, and President Garfield

In 1879, Redmond, along with his wife and three children, moved back to Swain County, N.C., and settled beside the Tennessee River somewhere near Almond. They built a cabin that had a commanding view of the approaching trails, and a trail and canoe landing behind it for quick getaways. This arrangement worked well on a couple of occasions and newspaper stories tell of Redmond’s dogs alerting him to revenuers approaching only to find that Redmond had exited the cabin through a rear door. One story claimed that he exited through the chimney but that seems a bit far-fetched. But he was only a man and no man has an infinite supply of luck.

On April 7th, while squirrel hunting with a double barrel shotgun, Redmond ran into a concealed party of six revenue officers led by Deputy U.S. Marshal K. S. Ray. They had come in the night before and hid waiting for him to come out of the cabin. According to most reports, he realized his peril, raised his gun to shoot, and was caught in a hail of buckshot and rifle bullets from 30 to 50 yards away.

From the Winston Leader, Winston-Salem, NC, Tuesday, May 03, 1881:

“They say that when he came out, gun in hand, they commanded him to halt when he raised his gun to fire, and they fired upon him, one ball striking the end of the barrel of his gun, knocking about three inches off, another going into the barrel of his gun. The concussion and wounds felled him to the ground. The striking of the end of his gun was all that saved his head from being blown off.”

I have heard accounts that Redmond was ambushed while hoeing corn but contemporary accounts of the encounter do not support this story. Even in Redmond’s humorous account of the raid which ran in the Yorkville Enquirer, he is carrying a shotgun when fired upon by the officers.

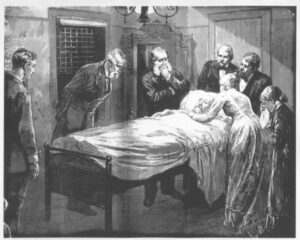

Accounts vary wildly but the consensus was that he was hit six times and some estimate that a dozen rounds went through his clothing. He fled and made it somewhere between 150 yards and a half mile before he fell, unable to rise. The shorter distance seems more believable. They took Redmond back to the cabin and Kay immediately sent for a doctor.

The doctor treated Redmond as best he could and forbade the officers from moving him for several days. This most likely saved the outlaw’s life. Then Redmond was moved to Charleston Township, now known as Bryson City, then on to Asheville, and finally to Greenville, S.C. to stand trial.

James A. Garfield, the 20th president of the United States, was shot at a railroad station in Washington, D.C., on Saturday, July 2, 1881, and died 79 days later on September 19. In Cobb’s book and in a couple of newspapers I came across items asking the same very reasonable question: how was it possible for Redmond to be shot six times in a wilderness, cared for by a lone country doctor, and survive while the president was shot once (really twice but one bullet only grazed his shoulder) in Washington D.C., cared for by a platoon of physicians with every medicine and technology of the day available and still perish.

The answer really comes down to three factors. One, as a wise man once explained to me, stuff happens. Two, if you have a choice of being shot at by six men from 50 yards away while shooting at them or running away versus being shot at with a .442 Webley British Bulldog revolver at 20 feet while unarmed and standing still, take your chances with having something to shoot back with, a greater distance and more mobility. Three, in a time when doctors did not believe in antiseptics or hand washing, a single doctor with a hands-off approach puts the odds in your favor.

Also in July of 1881 Billy the Kid (Henry McCarty), also known as William H. Bonney, the famous outlaw, and gunfighter, was shot and killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett. People like to point out that Redmond’s capture was featured on the front page of the New York Times, whereas Billy the Kid’s death was relegated to page eight. This is accurate, but I feel compelled to point out that Redmond’s capture received approximately 90 words, while Billy’s death received about 900 words.

The Trial, the Sentence, and Totaling Up the Scores

The trial began on August 25, 1881, and for the most part, was anticlimactic. Redmond was charged with eight counts of making, transporting, and selling illegal liquor, and two counts of conspiracy for the raids against Revenue Officers E. H. Barton and Wm. F. Gary. It seems essential to note here that Redmond was never tried for killing Deputy U.S. Marshal Alfred Duckworth in North Carolina.

Redmond was represented by General Albert C. Garlington, a prominent lawyer, state assemblyman, and former brigadier general in the state militia, and Isaac M. Bryan, Esq. Despite having this formidable legal firepower at his disposal, Redmond pleaded guilty to all charges. The Greenville News article notes that Redmond was able to pass up the steps unassisted on his crutches, was neatly dressed, clean shaven, and fanned himself with “a lady’s gaily-worked fan.”

Going by the newspaper reports, Redmond had a regular stream of visitors in the Asheville and Greenville jails. An article in the Yorkville Enquirer mentioned Redmond arranging for people to see him in Asheville for 25 cents a head provided they agreed not to talk to him.

One of Redmond’s Greenville visitors was none other than former revenue officer E. H. Barton, who Redmond either didn’t recognize or pretended not to recognize. When reintroduced to the man, Redmond is said to have remarked that Barton looked older than when he had seen him last. The conversation rapidly turned to accusations and recriminations. You know how it goes: you run into someone you haven’t seen in a while and the talk gets round to who shot who, who kicked who when their hands were tied, and who took whose money and horses. Pretty standard stuff. I can scarcely go to the grocery store without something like this happening.

An unnamed reporter or editor even totaled up Barton’s and Redmond’s scores which I paraphrased as follows:

Barton: Gave one capture, tying and kicking. Confiscated a team of horses and a wagonload of whiskey. Took an overcoat, a shawl, and $100 cash. Caused several nights and days of dodging.

Redmond: Gave one severe gunshot wound. Made one raid on Barton’s house and disturbance of family. Took $100 cash, and a horse. Caused a number of severe frights.

The reporter’s conclusion: The two wound up about even. I have a feeling both men would contest that interpretation.

At sentencing, General Garlington lived up to his reputation as a powerful and persuasive orator pointing out multiple reasons for the judge to be lenient with the prisoner. He mentioned Redmond’s many hardships growing up and his steadfast support of his family in the difficult days following the war. He also reminded the judge of the injuries that Redmond received during his capture.

“Thirteen balls penetrated his body and clothing,” Garlington said. “Four balls are now in his body, and he is injured perhaps for life. In all the fusillades fired on him, he numbers 162 shots. He is now suffering under his grievous wounds.”

Redmond was sentenced to 10 years at the federal penitentiary in Auburn, N.Y., and a fine of $2,600. The maximum sentence could have been 28 years.

Pardon And Epilogue

In 1884, South Carolina temperance reformers: Sally Taylor and Grace Elmore started advocating for Redmond’s pardon and release. Why they chose to pursue this is unclear. Stewart in his book points out that both women would later join the Daughters of the Confederacy, and they have just felt solidarity with an outlaw famous for boldly defying the federal government. The petition they circulated proved popular and U.S. Attorney General Benjamin Brewster agreed to transfer Redmond from Auburn to the S.C. state penitentiary in Columbia.

On May 16, 1884, President Chester A. Arthur, who succeeded James Garfield, gave Redmond a full and unconditional pardon at the request of Senator Wade Hampton and Attorney General Brewster.

He reunited with his family in Pickens County, then moved around the Upstate a bit before settling near Walhalla, S.C. Dietrich Biemann hired him to run a government distillery there. The whisky was branded as Redmond’s Handmade Corn Whisky and distributed by F. W. Wagener & Co., Charleston, S.C. The product was enormously popular.

Up until his death in 1906, Redmond lived a life without incident. He is buried in Seneca, S.C. His headstone bears his name, date of birth, date of death, and the legend “He was the sunlight of our home.” If anything I have read about this man is accurate, it is my deepest and most sincere hope that this one hand-carved sentence is true.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. Click on one of the social sharing icons below. Do you have a hot tip on a cold case? Got a topic you’d like to see covered? Want to nominate a moonshine king, Appalachian outlaw, legendary lawman, massive manhunt, or blue-ribbon bloodhound for a future post? Clue me in with an email to editor@blueridgetruecrime.com.

Check out my new book, Blood on the Blue Ridge: Historic Appalachian True Crime Stories 1808-2004, cowritten with my friend and veteran police officer, Scott Lunsford on Amazon. Buy it here! Download a free sample chapter here!

I also have a Substack newsletter, A History of Bad Ideas, where I write about poorly thought-out ideas, misguided inventions, and dire situations throughout history created by people who frankly should have known better.

Sources:

Bruce Stewart, King of the Moonshiners: Lewis R. Redmond in Fact and Fiction (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2008)

John Preston Arthur, Western North Carolina: A History from 1730-1913 (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Co., 1914)

Jim Bob Tinsley, The Land of Waterfalls: Transylvania County, North Carolina (Brevard, NC: J.B. and Dottie Tinsley, 1988)

Robert A. Cobb, The True Life of Maj. Lewis Richard Redmond, the Notorious Outlaw and Famous Moonshiner (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Co., 1881)

Edward B. Crittenden, The Entwined Lives of Miss Gabrielle Austin, Daughter of the Late Rev. Ellis C. Austin, and of Redmond, the Outlaw, Leader of the North Carolina Moonshiners (Philadelphia: Barclay & Co., 1879)

Pickens Sentinel, SC, Thursday, January 18 & 25, 1887 “Shooting Affray,”

Intelligencer, Anderson, SC, Thursday July 11 1878, Page 1 “Redmond’s Strange Story,” Thursday, October 17, 1878, “Redmond – Ladd Marriage Announcement”

New York Times, Monday, July 15, 1878, Page 5 “Democratic Moonshiners”

Asheville Weekly Citizen, Thursday, July 18, 1878, Page 2 “Bohemian and Brigand”

Winston Leader, NC, Tuesday, May 03, 1881 “Redmond the Outlaw”

Yorkville Enquirer York, SC, Thursday, August 18, 1881 Page 2 “The Redoubtable Redmond”

Greenville News, SC, Friday, August 26, 1881 “To 10 Charges”

Newberry Weekly Herald, SC, Wednesday, September 07, 1881, Page 2 “Redmond Sentenced”

Carolina Watchman, Salisbury, NC, Thursday, September 08, 1881, Page 4 “Hard to Understand”