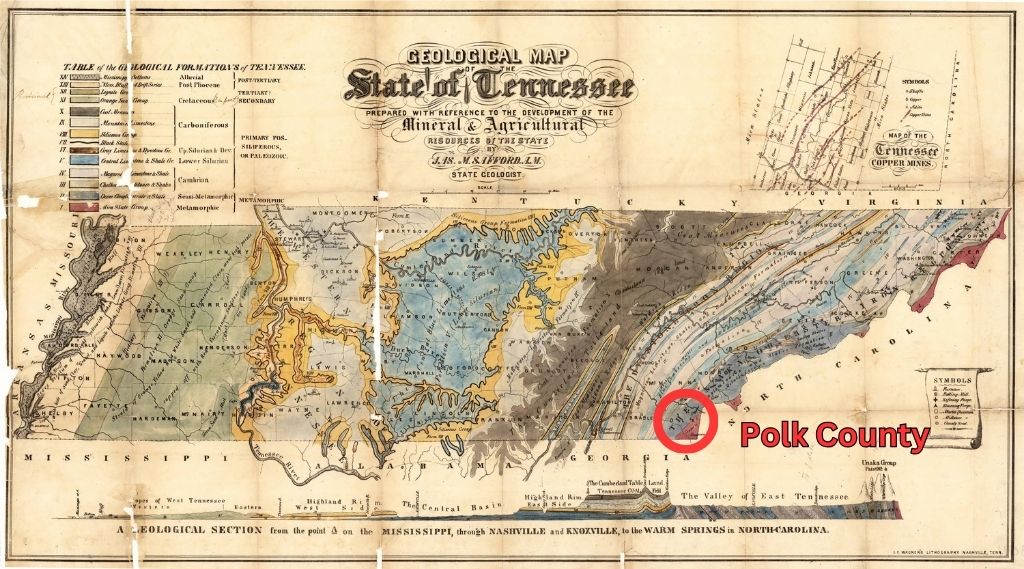

In 1900, Garrett Hedden was the most feared man in mountainous Polk County, Tennessee, a rural district in the southeast corner of the state. He was a well-known moonshiner who the local newspapers labeled a desperado and credited with killing eight men.

One killing, in particular, made citizens, marshals, and revenue men reluctant to cross the outlaw: the November 1898 shooting of his brother William, who was engaged in a drunken brawl.

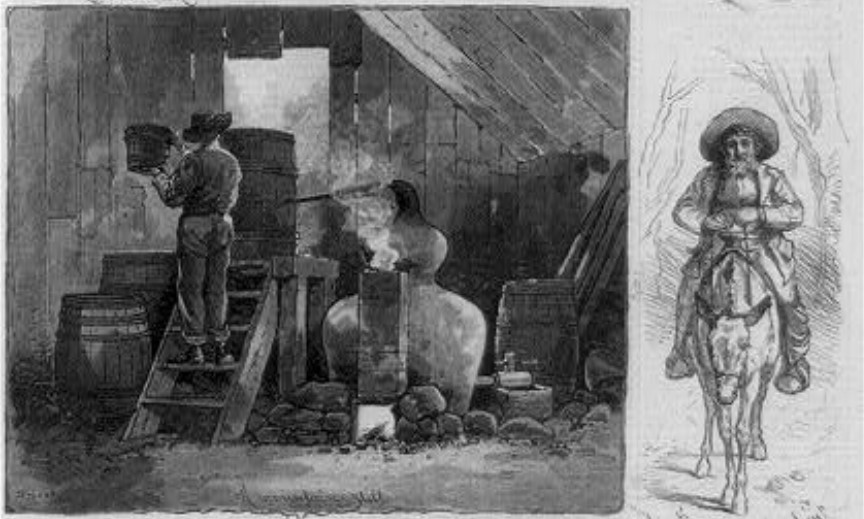

The most detailed account of the incident comes from journalist and adventurer Leonidas Hubbard, Jr., in his August 1902 article in The Atlantic magazine: “The Moonshiner at Home.”

“Garret Hedden and his brothers, Riley and Bill, and half a dozen other mountaineers, were at work in one of the little valleys. They had spent the greater part of the day splitting shingles while moonshine flowed freely. Half drunk, Bill Hedden became quarrelsome. He was a hard man to get along with at his best, and now he was looking for trouble in a way that promised to end disastrously. He started to quarrel with Garrett’s best friend. Garrett told him to stop. Bill paid no attention but grabbed his opponent around the neck and drew his knife. The knife was not far from the man’s throat when Garret’s rifle cracked, and Bill dropped dead.”

Hubbard, a Michigander, happened to be involved in a forestry project at a camp on the Ocoee River near Little Frog Mountain in 1901. Having read in the newspapers about Garrett, he sought out the outlaw and interviewed him. A pretty gutsy endeavor, given the moonshiner’s deadly reputation. Hubbard mentioned in the article that he dressed carefully when he set out to avoid being mistaken for a revenue agent.

“Dressed one day in garments that gave no opportunity for concealing weapons and which, therefore, obviated any danger of being mistaken for a revenue official, I threw a camera across my back and started for the neighborhood.”

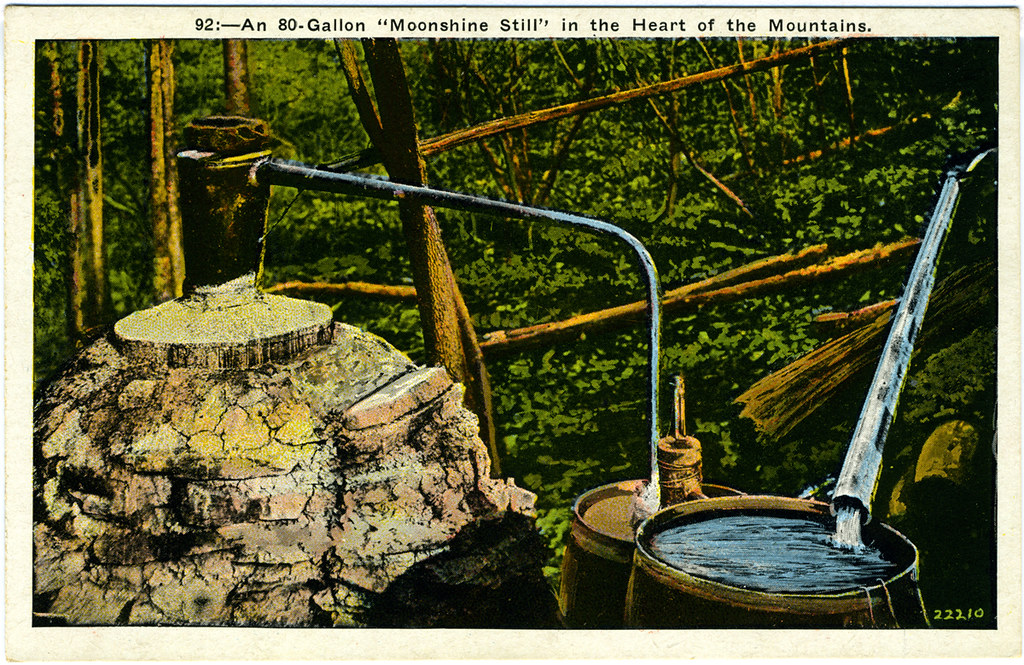

Moonshining was a Hedden family tradition, with all four sons, Bill, Garrett, Joe, and Riley, recognized as noted moonshiners, following in the footsteps of their father, John. For years, they ran a successful illegal distillery near Frog Mountain, protected by its distant wilderness location and Garrett’s well-known tendency to shoot holes into people he didn’t like.

Fusillade on Frog Mountain

In August 1900, chief raiding deputy of the Knoxville Internal Revenue office, J. B. Altom, traveled to Cleveland, TN, and gathered a seven-man posse of revenue agents, lawmen, and citizens for a raid on the Hedden settlement. They had definite information about the illegal enterprise and a guide to show them the way.

The posse left Cleveland at dark in a “private conveyance,” most likely a wagon or wagons, and spent all night traveling 35 miles, arriving at the banks for the Ocoee River at 6:00 the next morning. They left their driver and teams there. and proceeded “thence afoot over a rough, mountainous country until 9:00 am.”

Their target was Riley Hedden’s house and a moonshine still in a hollow near a clear, cold mountain spring 200 yards away. While the moonshiners went about their routine, gathering and chopping firewood and tending the still, the raiding party was able to slip in and arrest the gang.

Riley Hedden and Coot Owens were arrested at the house. Henry Norwood and Riley’s nephew, Gus, were arrested at the still. Officers noticed Gus making a peculiar call and attempting to signal someone. A few moments later, Silas Goforth walked in carrying a two-bushel sack of meal. He was also arrested.

According to the Knoxville Journal and Tribune, a 65-gallon copper still with 3,000 gallons of beer, as well as a good quantity of meal, mash, and whiskey, were destroyed. As the raiders handcuffed the men and moved them from the still to the house, everything was going according to plan until Garrett Hedden rode up on a mule carrying his Winchester across the saddle.

The following account is from Hubbard’s 1902 Atlantic article:

“Then, the revenues jumped into the house and behind the corncrib and began to shoot at Garret,” said Gus Hedden. “They shot seven or eight shots before he moved. Then he slid off his mule and laid down behind a log.”

Riley was being restrained by Constable C. B. Cash. He pulled Cash out into the open several times, either in the hopes that Cash would release him rather than risk being shot by Garrett or hoping to escape after Garrett hit Cash. Altom leveled his gun at Riley, who then abandoned his attempts to drag Cash into the path of one of Garrett’s bullets.

“The revenues threatened to kill us if we didn’t go out and get Garret to go away,” Gus continued. “We told ’em we couldn’t do nothing with Garret. So we all laid there behind the house, and Garret laid behind his log with his Winchester, scaring the revenues powerful nigh into fits. When it got too dark to see, they took us and sneaked out.”

The Knoxville newspaper article mentions Garrett firing on Deputy J. A. Pierce at close range and Pierce returning fire from inside the house with a double-barreled shotgun. It goes on to describe Garrett’s escape, saying:

“Garrett then made off up the mountain and indulged in the worst forms of blasphemy ever listened to. He cursed and swore at the officers and vowed the most horrible forms of vengeance on them.”

The party, along with its five prisoners, traveled back to the wagons and teams beside the river and arrived back in Cleveland shortly before midnight Wednesday. The skirmish further burnished Garrett’s reputation as an outlaw to be feared.

Riley was sent to the penitentiary for one year; Gus got four months in jail because it was his first offense, while Goforth and Norwood were given short terms for assisting an unlawful enterprise. Coot Owens was released without being charged. Apparently, he was just passing through and not part of the gang.

A Vow of Vengeance from the Edge of Death

In March of 1903, the Hedden family saga took an unexpected and dramatic turn that put them in newspapers throughout the country. Headlines included Story of the Mountains is Written in Blood from the Knoxville Journal and Tribune; Brother Kills Brother from the Biddeford Maine Daily Journal; Outlaw Stabbed by His Brother from the Birmingham Age-Herald; and Notorious Moonshiner Killed from the Butte, Montana, Tribune-Review.

Garrett and Riley Hedden had traveled through the town of Reliance. After leaving there, they went to George Parks’ store on Greasy Creek and bought a lunch of canned goods. The Journal and Tribune suggested that they both had consumed plenty of whiskey.

After eating their lunch, they started riding down Greasy Creek, where they became involved in a quarrel about Garrett killing his older brother, Bill, five years ago. Riley rode up beside Garrett, drew a long knife, and plunged it through Garrett’s body. The knife entered the right side of his chest and came out under the right shoulder blade. Garrett was still alive when the story went to press, but the article stated: “It is believed there is no chance for his recovery.”

There was speculation that Riley was afraid that the argument would end with Garrett shooting him just as he had shot Bill. Deciphering the motives of crimes committed by drunk men is not an exact science. Shocking as this turn of events was, it appears that the next part of the story was what caused its widespread circulation.

Garrett was taken home, and with his family gathered around him, he gave his eldest son, 10-year-old Charles Hedden, his revolver and made him swear to kill his uncle Riley as soon as he was old enough and big enough to complete the task.

Near the end of his article, Hubbard made a prediction about how Garrett’s life would end.

“Some day, he will walk out of the cabin, never to come back. If he is the man his neighbors believe, he will die with a smoking rifle in his hands and the lust of battle in his heart. But, however, he may die, his children grow up to carry weapons and distill forbidden liquors.”

Was Hubbard right about the fate of Garrett Hedden and his family? We’ll explore that in part two of The Meanest Moonshiner in Tennessee.

(Editor’s note: Hedden was spelled multiple ways in news reports and documents, including Henden, Hadden, Headen, and Heddon. Hedden seems to be the most often used, so I went with that throughout to avoid confusion.)

If you enjoyed this story, please consider sharing it with a friend or clicking on one of the social sharing icons above or below the post. Comments are always welcome. If you have a topic or crime you’d like to see covered, email me at editor@blueridgetruecrime.com.

Check out my new book, Blood on the Blue Ridge: Historic Appalachian True Crime Stories 1808-2004, cowritten with my friend and veteran police officer, Scott Lunsford on Amazon. Buy it here!

I also have a Substack newsletter, A History of Bad Ideas, where I write about poorly thought-out ideas, misguided inventions, and dire situations throughout history created by people who frankly should have known better.

Sources

Hubbard, Jr., Leonidas. “The Moonshiner at Home.” The Atlantic, August 1902.

Tennessean, Nashville, Wednesday, November 09, 1898, Page 3, “Killed His Brother”

Daily Times, Chattanooga, Wednesday, November 09, 1898, Page 5, “Polk County Tragedy”

Knoxville Sentinel, Friday, November 18, 1898, Page 7, “Fratricide”

Journal and Tribune, Knoxville, Friday, August 17, 1900, Page 5, “Biggest Revenue Raid Made in Some Years”

Tennessean, Nashville, Tuesday, August 21, 1900, Page 3, “Fusillade on Frog Mountain”

Morristown Republican, TN, Saturday, August 25, 1900, Page 1 “Moonshine Raid”

Journal and Tribune, Knoxville, Wednesday, March 11, 1903, Page 1, “Story of the Mountains Is Written in Blood”