Before Bonnie and Clyde, there was Irene and Glen.

On Friday, December 27, 1929, Corporal Brady Paul and Patrolman Ernest Moore of the Pennsylvania Highway Patrol left New Castle, PA, heading east on Butler Road. Paul operated the SHP motorcycle, and Moore rode in the sidecar. Walter “Glenn” Dague, Irene Schroeder, her brother, Tom Crawford, and her four-year-old son, Donnie, were driving west from Butler, PA. Neither party knew it, but they were on a collision course.

Before the day was over, one of the motorcycle policemen would be dead. The driver and passengers in the car would take months and years to find their way to startlingly different destinations: the electric chair at Rockview Penitentiary, a shootout with police in Cape Girardeau, and a launch pad at Cape Kennedy.

Earlier that morning, Dague and Schroeder had robbed a grocery store in Butler, about 27 miles from New Castle. Crawford stood watch outside, and Donnie waited in the car.

Schroeder and Dague had left the store manager, Wish Angert, and an elderly customer tied hand and foot and gagged in the back room. Angert was able to roll across the floor back into the store proper, and a customer entered the store and freed him. He immediately phoned the local police, and a new teletype system flashed an alert statewide.

Paul and Moore parked the motorcycle in a lane beside the road and began flagging down cars. They were looking for a man and woman, or possibly two men and a woman. Details were sparse. They had stopped five or six vehicles when a 1929 Chevrolet coach rolled to a stop just before noon. A man, a woman, and a young boy were in the front seat. The child was standing on the floor between the woman’s legs so he could look out the windshield. Another man sat in the back.

Paul asked the driver for his license, and Moore walked to the back of the car to check the license plate. Moore lifted his eyes from the plate and started to turn when he was startled by Paul bumping into him. Then he noticed the car’s driver, Dague, and the woman passenger, Schroeder, had gotten out of the car, and both were pointing revolvers at Corporal Paul, who was backing up with his hands partially raised.

Paul turned to him and said, “Pull your gun, Moore.” The officer proceeded around the car to get cover to draw his .38 caliber Colt Army Special revolver, with the intention of getting behind Schroeder and Dague. As he was doing this, Crawford fired at him through the open rear window from the car’s back seat with a .32 caliber automatic handgun. A bullet struck the tip of his nose. Still on the move, Moore finally cleared his weapon from the holster. Crawford fired again through the front window and missed. Moore continued around the car and crouched down in front of the radiator. When Moore lifted his head over the radiator, looking for a target, Crawford fired at him.

While Moore dodged bullets at the front of the car, Paul was in even more dire circumstances behind the vehicle. He found himself facing both Schroeder and Dague with his hands in the air, his weapon still in his holster, and no cover to speak of. He had to be desperately hoping for a break.

Besides Patrolman Moore, there were six witnesses to the shooting: residents of nearby houses and a truck driver, George Book, who gave Paul a ride to town to seek medical attention.

Eva Baldwin testified that when Paul was about 10 feet past the rear of the car, Schroeder fired at him. She stated that Paul had his hands at his sides when this happened. He may have tried to draw his revolver.

“I heard the shot and saw the smoke. I saw his body sway and his arm twitch,” Baldwin said. She did not see what happened next because she ran into the hall of her home to call the police.

“I Went Out Slow”

After Schroeder fired, Dague turned and ran to the right front fender of the car. Evidently, the sound of Crawford’s shots convinced him to go after Moore. The patrolman saw Dague coming, raised himself, took aim, and began squeezing the trigger. He was struck in the head by another bullet, and as he said in his testimony, “I fell backwards; I was dazed, just stunned, and I lost consciousness for a little while. I went out slow. I heard someone say as I was going down, ‘I got one.’”

The speaker was Schroeder, and she wasn’t talking about Moore, according to Rose Smith, Irene’s cellmate in the Maricopa County, AZ, jail, who testified that Irene told her this.

“She said she shot three times, and at the third time she shot, he grabbed his side, and when he grabbed his side, she knew she had hit him because he grabbed his side and went down,” said Smith. “Then she turned around and told Dague, “I got one of them.”

After Moore went down, witnesses saw Dague bend over him and shove him toward the middle of the road with his foot.

Schroeder returned to the car, and Corporal Paul got up off the road and ran to a nearby telephone pole. Another witness, Howard Zeigler, testified that Dague ran back toward Paul and shot at him from about 40 feet away as Paul was heading for the telephone pole. When Paul reached the pole, he leaned against it and opened fire on the car, which was pulling away.

Book helped Paul into his truck and brought him into town. He was taken to Jameson Memorial Hospital and died there at 12:55 p.m. He had three gunshot wounds. He was hit in the left arm, left leg, and abdomen. This bullet, which passed through his liver and right kidney, proved fatal.

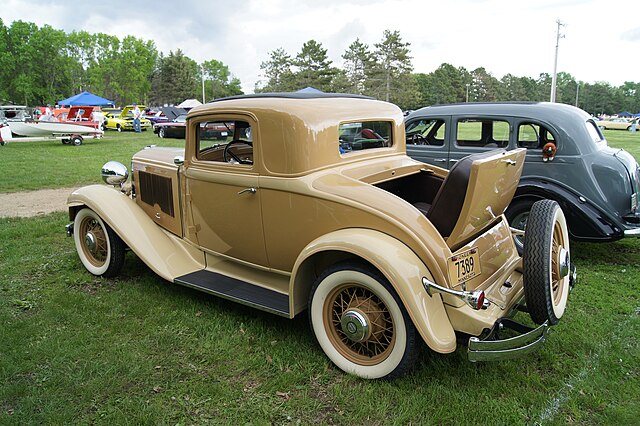

The fugitives abandoned the bullet-riddled Chevrolet in New Castle and carjacked a Chrysler roadster from Ray Horton. They drove to Wheeling, WV, where they stored Horton’s Chrysler in a rented garage, swapping it for a Pontiac coupe. They dropped off Tom Crawford in Wheeling and left Donnie with his grandfather, Joseph Crawford, in Benwood. Then Irene and Glenn embarked on a westward multistate odyssey of robbery, kidnapping, and shootouts with the police.

A Rolling Crime Scene

The hastily discarded Chevy contained an abundance of evidence, including several Wheeling, WV, newspapers, golf balls, a toy victrola, several items of children’s clothing and toys, a bar of Lifebuoy soap, Wish Angert’s bank book, and Mrs. Angert’s pocketbook, which were taken during the Bulter store robbery, spent .32 automatic and .32 S&W Long cartridges, or “shells,” and most importantly, a receipt from a Wheeling department store.

A clerk at the Wheeling store remembered Irene. Once the police had a name, they were able to track down Schroeder’s father and brother-in-law, which led them to Donnie. When questioned, Donnie said something like, “Mother shot a policeman.” A December 31, 1929, Associated Press story ran throughout the United States with headlines like the Boston Globe’s “Tot of 4 Says Mother Slayer” or the Fresno Bee’s “Boy Tells Police Mother Killed State Patrolman” or the Atlanta Journal’s “Tot Tells Police Mother Shot Officer.” The police now had names, not just vague descriptions. A bulletin went out nationwide.

The Chevy coach also provided physical evidence about the shootout. There were three bullet holes in the passenger side of the windshield made by Crawford firing at Moore from the back seat. There was one bullet hole on the driver’s side of the windshield. The same bullet traveled upward through the car’s roof. Moore may have gotten his shot off after all. There were three bullet holes in the rear of the car, put there by Paul shooting from his position beside the telephone pole.

Sargent Crowl of the Pennsylvania State Police examined Paul’s weapon after the shooting. He found one empty chamber and five empty cartridges. Many people in this time period left the chamber under the hammer empty so that if the revolver was dropped, it would not accidentally discharge. All 12 spare rounds in Paul’s belt were still there. Authorities were not able to inspect Moore’s weapon. When he regained consciousness, his revolver was gone. He would not see it again until he traveled to Arizona to identify Schroeder and Dague.

There was much debate about the presence of Schroeder’s son, Donnie, in the car. Was bringing him along on a robbery just bad parenting dialed up to 11, or was this a calculated strategy? With a child in the car, they would look much more like a family out for a drive than robbers evading the police. This may explain why the Pennsylvania Troopers were caught off guard.

Shoot Me in St. Louis

Schroeder and Dague’s next encounter with law enforcement came on the night of Saturday, January 4, 1930, when they were spotted by Patrolman William Kiessling in St. Louis around 9:45. In his trial testimony, he identified himself as a commissioned officer of the State of Missouri State Highway Patrol, but he appeared to have been walking a beat when he caught sight of Irene and Glenn driving slowly along Morgan Street.

The pair drove back around the block, but Kiessling was unable to stop them, so he flagged down a passing motorist and must have said something like, “Follow that car.” When he caught up with them, he blew his whistle and said, “Buddy, I want to question you.”

Kiessling said that he got within three feet of Dague when he produced a weapon and fired a shot “aimed directly at my heart.” The officer stepped into Dague to throw off his aim. At this point in his testimony, Kiessling requested to leave the stand and demonstrate what happened next rather than try to describe it. I may be reading too much into this, but the officer appeared to have a tendency toward the dramatic.

He explained that he tried to catch Dague in a Jujitsu hold but missed it and went with a hammer lock instead. While they were struggling, the officer said that he heard two additional shots but did not know where they came from. Their scuffling took them around the car, out of the street, and onto the sidewalk. Schroeder got out of the vehicle and pointed a gun at Kiessling.

“She pointed it directly at my face, and she said, ‘You son-of-a-*****, come on, or I will kill you.'” Kiessling said.

He shoved Glenn between himself and Irene and attempted to draw his gun, but Dague swung around and punched him in the jaw, and the officer went down onto the sidewalk. While he was down, Dague took his gun. By the time he regained his senses and his footing, they were driving away, and he fired at them with his other gun, which he carried as a spare, from a distance that he estimated at 40 or 50 feet.

The prosecutor produced a gun that had been recovered when the pair and Joe Wells surrendered to the Arizona posse and asked Kiessling if it was his. He was able to identify it by its serial number and a machine screw he had used to repair the handle. The officer also produced the uniform coat he was wearing that night. It had a bullet hole in the sleeve from Dague’s shot, and there were four holes in the back.

Kiessling also mentioned that Schroeder had been dressed in men’s clothing: blue overalls, a heavy men’s coat, and a cap and that her attempt to conceal herself in the car was one of the things that drew his attention in the first place. In his testimony, Dague admitted to taking a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson handgun from a police officer in St. Louis and shooting at that officer with the Colt revolver he acquired at the Butler, PA, shooting. Schroeder also described Kiessling’s encounter with them, admitted to pointing a gun at the officer during her trial, and said that they took the officer’s gun.

An article in the Friday, February 21, 1930, St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Patrolman Kiessling was fined $15 for neglect of duty, partially for losing the revolver during the January 4 incident. The article also mentions the holes in Kiessling’s coat and his commandeering a passing car to catch up with the fugitives.

A Con, A Kidnapping, and A Gunfight

Throughout their westward excursion, the pair often gave rides to hitchhikers. Near Pecos, Texas, they picked up Joe Wells, whose real name was Vernon Ackerman, who had been released from the McAllister, OK, penitentiary the day after Christmas 1929.

Wells was a bit of a character and perhaps a bit of a psycho. Schroeder testified that they picked him up because they saw him limping as he was walking along the road.

“I asked him if he was crippled, and he said yes, that he had a wooden leg,” said Schroeder. “He tapped on the leg, and I could hear the noise of wood.”

Later, Wells admitted to the pair that he did not have an artificial leg and that he kept a piece of wood stuck down in his shoe so he could make the sound.

“He told us later that he could get rides easier that way,” said Schroeder.

Wells went from hitchhiker to accomplice. I’m curious about how that conversation got started. Did Glen and Irene mention that they were on a nationwide crime spree, or did Joe ask them if they’d ever considered a side hustle in grand larceny?

The trio had worked out a con. When they came to a town, Glen and Joe would get out, and Irene would drive the car to a gas station. She would tell the attendant that she had no money and needed gas to get to her sick mother or sick child. This is what she was doing when Pinal County Deputy Sheriff Joe Chapman spotted her and asked to see the car’s title.

She honked the horn, and Dague and Wells walked up, drew their revolvers, and forced Chapman into the car. The men got into the car with him, and Schroeder got into the rumble seat, and they drove off.

Chapman managed to direct them in circles, and at one point, they got the car stuck in the Gila River and pressed him into service, digging the car out. He directed them to Chandler, where he thought officers would be waiting. Schroeder switched seats with Wells because he kept hitting Chapman with a blackjack.

“He was hitting Chapman over the head with a blackjack once or twice till Glenn, and I both made him stop and climb back in the rumble seat, and then he couldn’t touch him.”

Chapman’s hunch that deputies would be waiting in Chandler proved good. Maricopa County Deputies Lee Wright and Shirley Butterfield spotted the car, pulled alongside, blew the horn, and signaled for the car to pull over. When this proved ineffective, he rammed the car, bringing both vehicles to a halt in front of the San Marco hotel.

According to newspaper reports, this is when Wells fired at officers from the rumble seat of the fugitives’ car. The same report says that all three fired at the officers, but Schroeder later testified that the trio only had the two revolvers, and when captured, this was all the firearms they had. Regardless, there was plenty of lead flying.

The deputies returned fire; Wright was armed with a shotgun and Butterfield with a revolver. Chapman did the best he could in an impossible situation. He kicked the car door open and rolled out, attempting to drag Schroeder with him. Dague backed the car out, and they fled the scene.

Chapman and Wright were wounded in the shootout, Wright fatally. Deputy Butterworth was injured by flying glass from the car’s windshield. The outlaws must have been injured to some degree, but their wounds could not have been too severe, given that they later fled into the desert on foot.

The Last Roundup

At 4:00 p.m. on Tuesday, January 14, their ride came to an end. Officers found the Chrysler coupe abandoned beside the Gila River southwest of Phoenix. They crossed the river and fled into the desert. Deputies had no trouble finding their trail and surrounding them. The little band had taken up a position behind some boulders and fired on their pursuers for hours without hitting any of them. Finally, three deputies, aided by a young Indian named Sun Dust, managed to get behind them, forcing their surrender.

They found Kiessling’s Smith & Wesson revolver lying in the dirt about three feet from Dague and Schroeder and Moore’s Colt about the same distance from Wells. Between them, they had eight rounds of ammunition left. Deputy Sheriff Hance Coor reported finding 40 to 50 spent casings or shells in the area.

The arresting party consisted of five deputies and the young Indian. When they got down off the mountain, they found a posse of between 25 and 35 people armed with handguns and rifles waiting for them. Sheriff Wright described the group as being made up of deputy sheriffs, private citizens, and quite a few Indians. There was also mention of an airplane overhead, but it does not seem to have played a part in the capture. It would not have had any way to communicate with the officers on the ground anyway. The Associated Press published a photo of Schroeder on horseback with a deputy being brought across the river after the standoff.

Dague and Schroeder were extradited back to Pennsylvania to be tried for the murder of Corporal Brady Paul. Vernon Ackerman, alias Joe Wells, was tried in Arizona for the murder of Deputy Sheriff Lee Wright.

Schroeder’s trial began on March 12, 1930. The prosecution called 77 witnesses, including four from Arizona. The trial transcript was more than 1,000 pages long. She was found guilty of first-degree murder on March 21. Dague’s case began on March 24, and he received the same verdict on March 31. Both were sentenced to die in Pennsylvania’s electric chair.

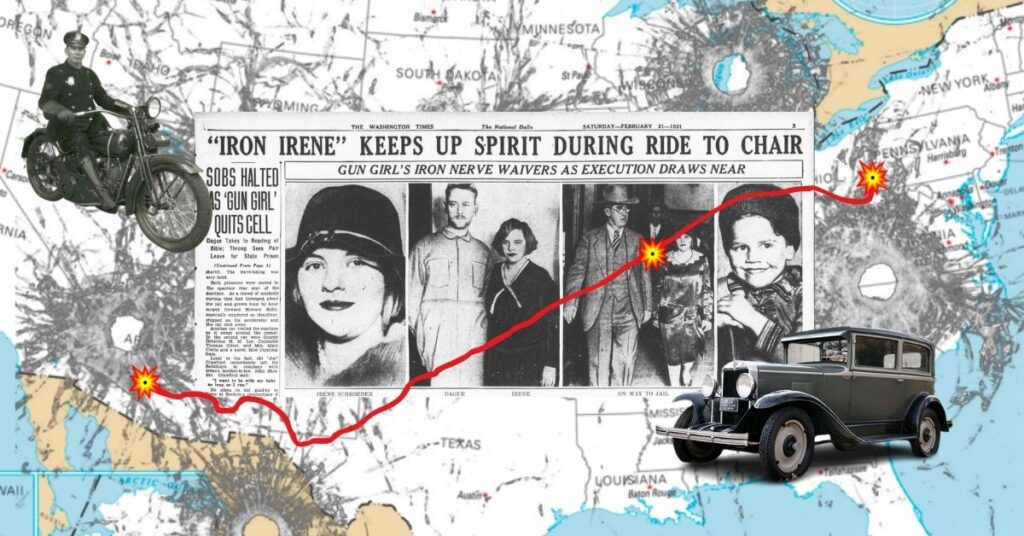

Iron Irene to the Last

On Feb. 23, 1931, at precisely 7:00 a.m., Irene Schroeder became the first woman to die in Pennsylvania’s electric chair. The following remarks come from Executioner Robert G. Greene in his book Agent of Death: The Memoirs of an Executioner.

“The most courageous person I have ever seen on the edge of eternity was a woman. Her name was Irene Schroeder, and she was only twenty-two. I believe she knew no fear.”

“With a certain dignity, she sat down. … While the straps and electrodes were being adjusted, she glanced at the witnesses, then closed her eyes. Two and a half minutes later, the prison physician pronounced her dead.”

Walter Glenn Dague, 34, followed her and was pronounced dead at 7:14 a.m.

Like many before him, Greene wondered why Glenn Dague, a car salesman, and Sunday school teacher, deserted his family to follow her from Wheeling, WV, to New Castle, PA, St. Louis, MO, Chandler, AZ, and finally the Rockview Penitentiary electric chair.

From Shootout to Moonshot

If you’ve been looking for a true crime story with an uplifting ending, today is your day. What happened to little Donnie Schroeder? He did well, about as well as you can imagine, maybe better. According to the book Family Secrets & Lies: Before Bonnie and Clyde There Was Gramma and Glenn by D.J. Everette, he joined the Army Air Corps, which became the Air Force, and flew in World War II and the Korean War. He became an engineer for defense contractor Rockwell International and worked at Cape Kennedy in the 1960s, supporting the Gemini and Apollo missions.

Donnie Schroeder was born Homer Edward Shrader on June 13, 1924, the son of Homer Shrader and Irene Crawford. Irene changed his name to Don Crawford Schroeder in 1926 after leaving his father. When Don enlisted in the Army Air Corps, he gave his name as Don Joseph Shrader. He had gone back to Shrader while living with his father after his mother’s death and took his grandfather’s first name as his middle name. According to Everette, Don wanted to distance himself from his mother’s notorious past.

Everette was Shrader’s estranged daughter from his first marriage. For decades, she was told that her father died in World War II. She discovered that he was still alive and was fortunately able to meet him before his death in 2010 at the age of 84.

Police Motorcycles

Reading about Paul and Moore arriving on the scene in a motorcycle with a sidecar made me curious about just how far back in history police motorcycles go. The answer was far further back than I thought.

Wikipedia credits Chief August Vollmer of the Berkeley Police Department with organizing the first official police motorcycle patrol in the United States in 1911. Harley-Davidson’s website states that the company’s first police motorcycle was delivered to the Detroit Police Department in 1908.

Milwaukee Police Historical Society’s Motorcycle Unit webpage notes that the Milwaukee Department had two motorcycle patrolmen in 1908 attached to its central station. By 1920, the Milwaukee motorcycle unit rose to 13 patrolmen.

Unfortunately, I was not able to turn up information about the motorcycles used by the Pennsylvania Highway Patrol in 1929.

Epilogue

Ernest Moore later advanced to the rank of captain and commanded Highway Patrol Troop B in Washington, PA.

Joe Chapman, the deputy sheriff who Schroeder, Dague, and Wells kidnapped, started working for the Arizona Livestock Board in 1931 and served on the State Board of Cattle Inspectors for 35 years. His obituary notes that he came to Arizona in a covered wagon as an infant. In addition to being a deputy sheriff, he also served as a Spanish interpreter for the court.

Sheriff Charles Wright went on to become the chief of police and later the assistant chief for Phoenix. He was a law enforcement officer for 40 years. In addition to being sheriff of Maricopa County, he was a deputy U.S. Marshal in Washington and Oklahoma. He sometimes acted as a court interpreter and was credited with speaking seven Indian dialects.

Tom Crawford and an accomplice, John Huff, were killed in a second-floor flat in Cape Girardeau, MO, in early January 1933. They had robbed a restaurant in Morehouse earlier in the day and got into a shootout with seven police officers. They lost. Crawford was identified by his fingerprints.

Vernon Glen Ackerman, alias Joe F. Wells, received a life sentence on June 2, 1930, for his part in the shooting death of Deputy Sheriff Lee Wright in the Chandler, AZ, gunfight on January 13, 1930. He died in Arizona State Prison on October 20, 1931, of heart disease.

I am deeply indebted to the Lawrence County Historical Society for images, documents, and assistance. I could not possibly have written this post as completely or as accurately without them. Please consider visiting them in person or on the web.

I would also like to thank the Milwaukee Police Historical Society for allowing me to use some of their Motorcycle Unit images.

Check out my new book, Blood on the Blue Ridge: Historic Appalachian True Crime Stories 1808-2004, cowritten with my friend and veteran police officer, Scott Lunsford on Amazon. Buy it here! Download a free sample chapter here!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. Click on one of the social sharing icons below. Do you have a hot tip on a cold case? Got a topic you’d like to see covered? Want to nominate a moonshine king, Appalachian outlaw, legendary lawman, massive manhunt, or blue-ribbon bloodhound for a future post? Clue me in with an email to editor@blueridgetruecrime.com.

Sources

Lawrence County Historical Society

Milwaukee Police Historical Society

Commonwealth v. Irene Schroeder, alias Irene Schrader, March Term 1930, 53rd Judicial District, New Castle, PA.

Everette, D.J. Family Secrets & Lies: Before Bonnie and Clyde There Was Gramma and Glenn. Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse, 2013.

Greene, Robert G. Agent of Death: The Memoirs of an Executioner. New York, NY: Dutton, 1940.

Corporal Brady Clemens Paul – Officer Down Memorial Page

Pennsylvania State Police: Memorial Wall: Corporal Brady C. Paul

Deputy Sheriff Lee Wright – Officer Down Memorial Page

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Saturday, December 28, 1929, Page 5, “State Police Block Highways to Find Slayers” (Photo of car windshield)

Mount Carmel Item, PA, Monday, December 30, 1929, Page 1, “Seek Highway Killers”

Arizona Republic, Phoenix, Tuesday, January 14, 1930, Page 1, “Kidnap Florence Deputy”

Arizona Republic, Phoenix, Wednesday, January 15, 1930, Page 1, “Bandits Taken After Fight”

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Friday, February 21, 1930, “Patrolman Kiessling Fined $15 for Neglect of Duty”

St. Louis Star and Times, Thursday, March 13, 1930, Page 1, “Policeman Here Witness in East in Woman’s Trial”

Arizona Daily Star, Tucson, Tuesday, June 03, 1930, Page 2, “Ackerman Sentence is for Life Term”

Tampa Times, Florida, Monday, February 23, 1931, Page 1, “Pennsylvania Woman Slayer Is Executed.”

Los Angeles Times, Wednesday, October 21, 1931, Page 20, “Arizona Slayer Dies in Prison”

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Monday, January 9, 1933, Page 12, “Trigger Girl’s Brother Slain by Policemen”

Arizona Republic, Phoenix, Saturday, July 10, 1943, Page 7, “Charles H. Wright, Peace Officer, Dies”

Arizona Republic, Phoenix, Saturday, April 08, 1967, Page 14, “Casa Grande Rites for Joe Chapman”

Arizona Republic, Phoenix, Saturday, May 22, 1999, Page 39, “1930 Gunbattle in Chandler” By Dennis Wagner

Orlando Sentinel, FL, Saturday, February 01, 2010, Page A16, Don J. Shrader Obituary

Orlando Sentinel, FL, Saturday, February 27, 2010, Page B10, Donna May Shrader Obituary

My Great Grandfather, Madison Clinton Kennedy, was the Lawrence County Jury Commissioner on this Trial. The trial was during the Great Depression. My Grandfather, Thomas C. Kennedy, was on the Jury for the trial. I remember my father telling me that there was some controversy about who shot Brady Paul introduced by the Defendant, but the jury didn’t buy it, and convinced her anyway My Grandfather said she was such horrible person. John Kennedy

John, thanks for sharing the information and your connection to the case. I just finished doing a podcast about it. https://tinyurl.com/d2r3sjsb

Best regards,

AD