Revenue officers knew there was a still near Hester & Thompson’s mill, in the northern part of Wake County, along the banks of the Neuse River in an immense cane break known as the “Harricanes,” a three-by-five-mile area covered by a dense growth of cane from seven to 10 feet high.

They’d been searching for a “blockade still” there for years and had discovered several places where stills had been recently pulled out. They had raided every foot of land for a mile around the mill without success.

In November 1902, Revenue Agents Starkey Hare and Dr. J. W. Perkins were raiding near the mill when they noticed large flocks of wild ducks below the mill dam on the river.

They decided that it was a bad day to raid but a good day to duck hunt and took up a position on the riverbank.

The men noticed that the ducks were vigorously feeding on something on the water’s surface. Investigating, they discovered that the ducks were eating cornmeal bran.

Cooked cornmeal bran.

There was only one thing this could be: slop from a moonshine still that had been emptied into the river. There was no bran above the mill, so there had to be some connection between the mill and an illicit distillery.

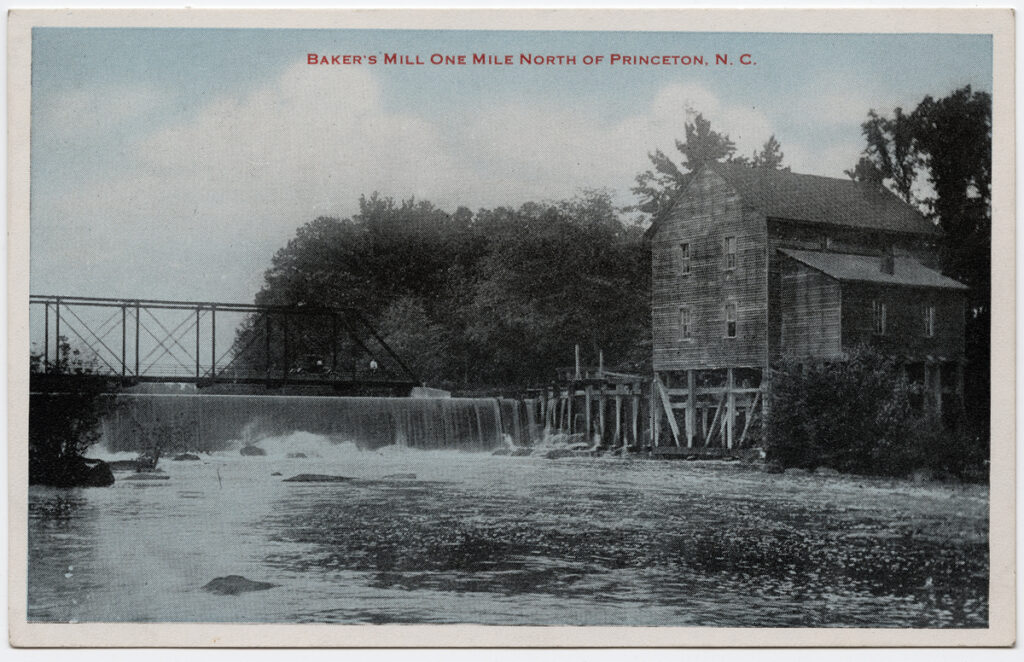

The mill-house was a two-story wooden building built into the side of a slope beside the dam and surrounded by woods. In cold weather, it was heated by a huge fireplace. The dam across the river was about fifteen feet high and eighty yards long. To prevent logs from catching on the dam, a plank bed six feet wide was built to aid the logs over the dam.

Hare and Perkins decided to stake out the mill and see who and what came and went. They saw the mill operator, Ray, and a woman named Huldah Nines come and go. For several days, there would be no bran floating on the river; other days, there would be. They had no idea where it was coming from.

They did have one break. Traveling up and down the river, the agents discovered a landing with kegs floating in the water. They opened one and found it full of corn whiskey. They left the kegs just as they’d found them.

On one hand, they now knew they were on to something. On the other hand, they didn’t know where the kegs came from either.

Vanishing Acts and Smoke Signals

Convinced that the mill was at the heart of the matter, they returned at night, broke into the mill, and searched the building. It turned out that the mill was, well, a mill. There was no sign of an illegal distillery.

That night, Nines returned, unlocked the mill, and went inside. The officers thought they had her now.

The agents waited a few minutes, slipped into the building, and searched for her. She was nowhere to be seen. The woman had vanished. They waited inside until nearly daylight and then returned to their outpost in the woods.

When it became light, Hare and Perkins saw a thick column of black smoke rising from the mill’s chimney even though the fireplace inside the building had been empty and cold.

After dark, Hare and Perkins again entered the mill-house and hid. From this vantage point, they saw Huldah Nines and a man by the name of Tilly arrive at the mill, walk to the dam, and vanish through the pouring water.

The pair didn’t return.

The next night, Hare and Perkins tried it themselves. After getting soaked by water from the dam, they emerged on the other side and found a door in the side of the hill. It was securely locked. So they wet some flour into a paste, took an impression of the keyhole, went back to Raleigh, and had a key made.

They weren’t all that confident in a key made from a quick-and-dirty flour impression, so they brought the locksmith, one T. F. Brockwell, back with them. The article does not tell us whether he was an enthusiastic member of the expedition or if they had to wrestle him and his toolkit into a wagon.

On their return to the mill, they found the river full of ducks and saw smoke pouring out of the chimney. The officers knew the still must be running in full blast.

Behind The Door

At nightfall, Nines and Tilly came out and went off. The officers and Brockwell tried the key, but it was not a good fit. After considerable labor with Brockwell’s tools, the key did its work, and when they finally opened the door, it revealed a concealed underground entrance.

It led to a six-foot-long tunnel that opened into an underground room equipped with a complete whiskey distillery. The chamber had been dug into the hillside and shored up with timber. Water moved from the dam to the still, and then back outside, carrying the slops that attracted the ducks. Smoke from the still’s furnace rose through the mill-house chimney, and a hole in the ground overhead, hidden by vegetation, provided ventilation.

After two hours of waiting, the officers heard the door open. In walked Huldah Nines. Hare and Perkins hid in a dark corner as she threw off the rubber coat she’d worn to pass through the pouring river water. She then commenced to kindle the fire under the furnace.

At this point, Hare and Perkins stepped into the open.

Nines looked at them in utter astonishment and said, “Well, well, well! I’ve been running this still for ten years, and I never expected you to find it.”

She told them the distillery was the handiwork of a man who had been dead for several years. He’d taught her everything. She took a keg, rolled it to the door, put it in the river, and turned it loose. “You’ll find that keg in a few minutes at a landing place about four hundred yards down the river,” she said.

The agents already knew where the keg would fetch up.

Hare and Perkins took the woman moonshiner off to jail. As they drove to Raleigh, they offered her a deal. If she helped them arrest her accomplices, they’d let her off. Huldah Nines refused.

She said she’d take her punishment, but she’d never betray their trust.

From the Friday, February 06, 1903, Gaston Gazette:

“Huldah Nines, a white woman, pleaded guilty to running a blockade still and was sentenced at the recent December term of the United States court in this city to two years in the penitentiary at Nashville, Tenn., where she now is.”

From Moonshiner to Mill Worker

It appears that Nines served about a year in the federal penitentiary.

An article from the Monday, Dec. 14, 1903, the Nashville Banner carried this item about Huldah’s release from prison.

WOMAN MOONSHINER.

“Huldah Nines, the woman moonshiner from North Carolina, who has been serving a term as a Federal prisoner in the Tennessee penitentiary, was released today and will return to North Carolina. She will probably go to Raleigh and undertake to secure work in one of the cotton mills there, as she has made a good hand in the knitting mills in the prison and goes out much better prepared to earn an honest living than when she entered.”

An article from the Tennessean published the same day tells us that she would have been released earlier, but lost three days of “good time” for passing notes with a male prisoner. In the final paragraph, the paper quotes her as saying that she had “got ernuff o’ them stills.”

If you enjoyed this story, please share it with a friend.

For more Appalachian true crime stories, check out the Blue Ridge True Crime Podcast.

Or subscribe to the Blue Ridge True Crime Substack.

Sources

wakeforestmuseum. “THE WHISKEY WAS UNDERGROUND!” Wake Forest Historical Museum, 16 Jan. 2018, wakeforestmuseum.org/2018/01/16/the-whiskey-was-underground/

Gaston Gazette, Gastonia, NC, Friday, February 06, 1903, Page 1, “The Still was Underground”

The Tennessean, Nashville, TN, Friday, June 05, 1903, Page 12, “Woman Moonshiner”

The Tennessean, Nashville, TN, Monday, December 14, 1903, Page 6, “Quits Prison To-Day”

Nashville Banner, TN, Monday, December 14, 1903, Page 10, “Woman Moonshiner”